The Wandering Gaines' go to Africa! We are going to Cameroon to serve in the Peace Corps June 2011 to August 2013.

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

An end of it

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Central Africa’s Bushmeat Crisis

by Sean Denny

(We weren't able to include some of the images and content from the original document, but feel free to e-mail us for the full PDF.)

What is the Bushmeat Crisis?

The bushmeat trade is the commercialized killing, selling, and trafficking of wildlife for consumption. The trade in Cameroon is much larger than many people realize. For example, millions of pounds of bushmeat in Cameroon are not consumed in the rural areas where wildlife is hunted; instead, this wildlife is smuggled from rural villages and forests—often on logging trucks—to urban markets of all sizes, including those of Yaoundé and Douala. In fact, 90-100 tons of bushmeat arrives in Yaoundé every month for sale. And the numbers surrounding the entire Central African bushmeat trade are staggering. For example, it is thought that at least 2-3 billion pounds of wildlife is extracted from the forests of Central Africa each year for the bushmeat trade. Although a significant amount of this wildlife is consumed at the local level, bushmeat hunting in the last several decades has become increasingly commercialized, as well as increasingly illegal, which has resulted in a dangerously unsustainable commercialized trade.

In short, the bushmeat trade is one of the world’s largest and most intense threats to our planet’s wildlife, and the bushmeat trade of Central Africa is the largest of its kind in the world. Illegal bushmeat hunting in the region is nothing short of a disaster to conservation efforts. In due time, the bushmeat trade may spell the end of some of Cameroon’s—and Africa’s—most spectacular wildlife.

From top left, clockwise: A putty-nosed monkey for sale at a market in Batouri, East region; An African dwarf crocodile, killed for the bushmeat trade, Southwest region; Monkey stew and meat (including a monkey skull), East region; Smoked monkey bushmeat, Littoral region. Photographs: © Sean Denny.

From top left, clockwise: A putty-nosed monkey for sale at a market in Batouri, East region; An African dwarf crocodile, killed for the bushmeat trade, Southwest region; Monkey stew and meat (including a monkey skull), East region; Smoked monkey bushmeat, Littoral region. Photographs: © Sean Denny.It is well known among biologists that Cameroon is a marvel of biodiversity. The country not only contains an unusually high number of animal and plant species, it also contains a large number of animal species that live nowhere else on Earth, or only in Cameroon and one of its neighboring countries. This means that unsustainable bushmeat hunting in Cameroon has the potential to wipe out entire species, particularly rare and endangered primates, of which there are many in Cameroon.

Animals in Cameroon most threatened by the bushmeat trade:

Monkeys (all species)

Chimpanzees

Gorillas

Forest Elephants

Bongos and Sitatungas (antelopes)

Forest Buffalo

Goliath Frogs - largest frog on Earth

Water Chevrotain (an antelope)

Pangolins (all species)

African Dwarf Crocodiles

Fruit Bats

Some Mammals of Cameroon

The Cross River gorilla is among the rarest animals on Earth, with only 200-300 invdividuals alive today. This animal is only found in small portions of the Southwest and Northwest regions of Cameroon, as well as the Cross River State of Nigeria.

Drills are consistently ranked as one of the most endangered primates in Africa, and their numbers are still declining. Mandrill (Rafiki from the Lion King) populations are also declining rapidly as a result of bushmeat hunting. Each of these species is found in only three countries, yet Cameroon contains them both.

The western lowland gorilla is listed as critically endangered. In addition to bushmeat hunting, Ebola outbreaks are seriously threatening the long-term survival of this iconic species.

Forest elephants (a separate species from savannah elephants) are being mercilessly slaughtered across Central Africa. In the last 10 years, 62% of all forest elephants on Earth were killed for their ivory or meat. In another 10 years, the species could be gone.

The excerpt below is from a document published by The Bushmeat Crisis Task Force. The excerpt provides further information about the bushmeat trade and It also mentions why large-bodied species are especially threatened by bushmeat hunting.

“Deforestation still threatens habitat in tropical forests. But when the equivalent of 4 million cattle in wildlife—many of which are endangered species—are hunted and eaten each year in Central Africa, tropical forests face a more immediate threat, known as the “empty forest syndrome.” It turns out we can “defauna” a forest quicker than we can “deforest” it. Tropical forests, in contrast to tropical savannas, are particularly susceptible to over-hunting because they harbor less wildlife—by at least an order of magnitude. Hunting intensity is increasing as demand for meat increases with human population, as new, more lethal, hunting technologies such as wire snares and firearms are widely adopted, and as roads and vehicles open once isolated forests and significantly reduce hunters’ transportation costs. Hunters consider all wildlife fair game; and they prefer large animals such as apes, elephants and large antelopes because they generate the highest returns on investment. They will continue to take the more profitable large animals whenever they can, regardless of their scarcity, even when other smaller wildlife are sufficiently abundant to make hunting returns economically viable. ”

Logging companies in Cameroon are creating new road networks in once-remote forested areas, giving hunters unprecedented access to some of Cameroon’s last remaining healthy forests and their large-bodied wildlife. The trucks in this photo are coming from the forests surrounding Lobéké National Park. Lobéké is one of Cameroon’s most remote protected areas, but it is increasingly suffering from large-scale poaching. Photograph: © Sean Denny.

Logging companies in Cameroon are creating new road networks in once-remote forested areas, giving hunters unprecedented access to some of Cameroon’s last remaining healthy forests and their large-bodied wildlife. The trucks in this photo are coming from the forests surrounding Lobéké National Park. Lobéké is one of Cameroon’s most remote protected areas, but it is increasingly suffering from large-scale poaching. Photograph: © Sean Denny.Steps YOU can take to avoid participating in the bushmeat trade during your service in Cameroon:

1. Never eat endangered or near-endangered species. These include all monkey species, chimpanzees, gorillas, elephants, African dwarf crocodiles, pangolins (they look like a bizarre, scaly anteater and are called “katabeef” in pidgin), forest buffalo, goliath frogs, and any antelope/deer species (because you don’t know what type of antelope you’re eating—it might be an endangered species)... OR, even better, choose to not eat any kind of bushmeat.

2. Never eat bushmeat being sold in an urban setting, including small towns and bus stops along roads. Eating bushmeat in an urban setting directly supports commercial bushmeat hunting.

3. Never buy any animal or animal part, including animal skulls and skins. Doing

so only increases incentives for hunters to kill and sell more wild animals. Even if you see a live endangered animal for sale, never buy it. You can take action by calling LAGA or the Limbé Wildlife Center (see below).

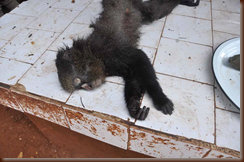

4. Never keep a wild animal as a pet, especially a monkey. Primate pets are almost always orphans whose parents were killed for the bushmeat trade. Many PCVs may like the idea of having a pet monkey, but keeping monkeys as pets sets an unfortunate example, as people may view a PCV’s enjoyment of keeping an orphaned pet as support for the killing of animal parents. Although this obviously is not true, it is easy for Cameroonians to misinterpret our motivations and attitudes, and it is very likely to happen in this case, regardless of what you say.

5. Never go bushmeat hunting.

A blue duiker and flat-headed kusimanse for sale at a market in the Southwest region.Photograph: © Sean Denny

A blue duiker and flat-headed kusimanse for sale at a market in the Southwest region.Photograph: © Sean DennyBushmeat and livelihoods An Important Topic

When learning about the bushmeat trade, it is necessary to be aware of the fact that bushmeat is an important source of protein for millions of impoverished people living in the rain forests of Central Africa. Additionally, hunting and selling bushmeat can be a valuable source of income in economies offering few other alternatives. To ignore these realities would undermine the complexity of the bushmeat crisis and it would fail to address the issue in its entirety. From a development and humanitarian point of view, not all bushmeat should be considered bad. For example, cane rats, rat moles, porcupines, snakes, and snails (and fish!) are good and reliable sources of protein, as well as the abundant blue duiker antelope (frutambo). These animals reproduce quickly enough to withstand hunting pressures. But there are species that do not reproduce quickly enough (for example by having long pregnancies and long maturation periods) nor live at high enough numbers for their populations to survive the demand. These are the species being pushed to either global extinction or localized extinction in Cameroon.

While legal subsistence hunting may be justified, illegal and commercial bushmeat hunting must be stopped—or, in the case of commercialization, at least severely reduced in villages while fully stopped in all urban settings, including the smallest of towns. This is necessary when one considers both the unsustainable nature of the trade and the welfare of human beings that rely on bushmeat for food. Bushmeat is a resource that is being depleted at an alarming rate. Its depletion will result in a much reduced food supply in the coming years for hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of Cameroonians. Moreover, tropical rain forests rely on fruit-eating animals to disperse and germinate seeds, which allows these forests to regenerate.

Cameroonian forests need their wildlife, especially fruit-eating animals such as primates, elephants, antelopes, hornbills, and fruit bats. Furthermore, many Cameroonians are heavily dependent on Cameroon’s forests for ecosystem services (i.e. the production of clean water, food, fuelwood, building materials, tools, medicine, etc.). Therefore, not only are wild animals in Central Africa valuable for their major contributions to African and global biodiversity, they also have crucial ecological roles in productive forests and are currently a vital food resource for many poor, rural-dwelling Africans.

Lastly, all PCVs come to Cameroon with the intentions of improving the lives of the poor and to promote sustainable solutions to poverty. The sustained health of natural ecosystems is crucial to the livelihoods of almost all impoverished people, who are often deeply reliant on ecosystem services for subsistence living. It is therefore in all of our interests to promote the health of Cameroon’s wildlife and ecosystems. An easy way for a PCV to start this process is by removing him or herself from the bushmeat trade (see above), educating others about the unsustainable nature of the trade, and safely alerting authorities to illegal activities threatening the survival of Cameroon’s wildlife.

Wildlife Crime: The Bigger Picture

Wildlife Crime is a grave problem throughout all of Africa, and indeed throughout the entire world. A great deal of wildlife crime in Africa is of course connected to the bushmeat trade, but wildlife crime goes further to include the poaching, capturing, and trafficking of animals and animal parts for ivory, traditional medicine, pelts/skins, trophies, pets, artwork, and souvenirs. A large part of the wildlife trade, particularly the ivory trade, is driven by China’s immense and growing demand for wild animals and their parts. Buyers of illegally obtained wildlife, however, are found throughout the entire world. The chain, of course, starts in countries that contain the sought after wildlife, such as the country of Cameroon.

Wildlife crime is rampant in Cameroon. Cameroonian foresters and park rangers will often turn a blind eye to wildlife crime—or become active in it—if the right amount of money is promised. In fact, it is not uncommon for park rangers and government officials in many African countries to be involved in poaching activities and other acts of wildlife crime. Corruption itself may be the single greatest threat to our planet’s wildlife. Wildlife laws are rarely enforced in underdeveloped nations even though these countries often harbor the most threatened of species. Today, a huge number of customs and port authorities—and other government officials—are bribed to ensure their complicity in the illegal wildlife trade. In fact, reveling in their triumph over authorities, traffickers and dealers will sometimes boast about the success of their global undetected trading networks.

Indeed, poachers, traffickers, and dealers of wildlife are disturbingly successful. The international wildlife trade is now the third most profitable form of organized crime in the world (after narcotics and human trafficking). An equally concerning fact is that the money generated from the trade frequently goes to funding rebel or government militias in Africa. In fact, one of the largest events in wildlife crime in decades was recently perpetrated by a notorious Sudanese militia, the Janjaweed. During January and February of 2012, the Janjaweed killed three-hundred and fifty plus elephants in Cameroon’s Bouba Ndjida National Park.

This atrocious event in more detail below.

Sadly, wildlife crime is growing and the technology used by poachers is becoming increasingly sophisticated and lethal. Poachers are now using helicopters to map out the movements of large animals (such as elephants and rhinoceroses) in national parks. Military weapons, including machine guns, mortars, and grenades, are being used to kill both wildlife and park rangers. In many parts of Africa, it seems that a war has broken out over the continent’s wildlife.

Despite rapid and expansive urbanization in Africa, and the concomitant destruction of its natural habitats, wildlife crime is the most significant and immediate threat to Africa’s wildlife. As a PCV in Cameroon, it is important to be educated about these destructive activities. The following page discusses how you can report wildlife crime if you come across such activities during your Peace Corps service in Cameroon.

Reporting Wildlife Crime in Cameroon: The Choice is up to You

At some point during your service in Cameroon, you are likely to come across an act of serious wildlife crime. If you wish, you can report the case to the Last Great Ape Organization (LAGA), an NGO in Cameroon that partners with the Cameroonian government to take action against wildlife crime OR you can report the case to the Limbé Wildlife Center, a rescue center for orphaned wildlife. Below are some good examples of cases that you can report to LAGA and/or the Limbé Wildlife Center (LWC).

Cases of primates being illegally hunted or sold or illegally kept in captivity. Contact the LWC or LAGA if you see a live or dead endangered primate for sale, or an endangered primate being kept as a pet. You can also contact these organizations if you have any other substantial knowledge regarding the hunting and selling of endangered primates. Endangered primates include chimpanzees, gorillas, drills, mandrills, and other lesser-known species, such as colobus monkeys and the rare De Brazza’s monkey. If you give the LWC or LAGA a detailed description of a particular primate, they can help you determine the species. Note: A protected wild animal is being illegally kept in captivity if it is being kept anywhere outside of an established wildlife/rescue center.

Cases of other wildlife being illegally hunted, sold, or kept in captivity. See the end of this document to learn which animals are illegal to kill, sell, or posses in Cameroon.

Cases related to elephant poaching and/or the selling of ivory. If you have knowledge of elephant poaching activities or the selling of ivory, call LAGA. Additionally, if someone offers you the opportunity to purchase ivory (this has happened to PCVs before), call LAGA and report the case.*

Left: A male chimpanzee illegally kept captive in a village in the Southwest region of Cameroon. Photograph: © LWC

Left: A male chimpanzee illegally kept captive in a village in the Southwest region of Cameroon. Photograph: © LWC*It is important to know that both LAGA and the LWC will never expose your identity if you report a case. Always keep in mind, however, that the safety of an animal should never be prioritized above your own. Therefore, you are encouraged to alert LAGA and the LWC to wildlife crime at your discretion. For clarification on this issue, you are welcome to call either of these organizations.

Vallee Nlongkak, Yaoundé

Email: ofir@laga-enforcement.org

Tel: 99.65.18.03

The Massacre at Bouba Ndjida, Cameroon

Photograph: © WWF Cameroon

Photograph: © WWF CameroonHighly intelligent, social, emotional, and immensely powerful, elephants are surely among the most magnificent creatures on Earth. Yet the future of elephants in Africa is disturbingly bleak. This elephant (above) was one of three-hundred and fifty plus elephants that were slaughtered in January and February of 2012 inside Bouba Ndjida National Park, located in the North region of Cameroon along the country’s border with Chad. This massacre was one of—if not the—worst poaching events in the world in decades. It was perpetrated by the Janjaweed, a Sudanese militia that fights on horseback, mostly in Darfur.

In early 2012, the Janjaweed road on horseback from Sudan, through the Central African Republic and Chad, and into Bouba Ndjida National Park, where they used machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, and other powerful weapons to kill hundreds of elephants. Chainsaws were used to cut off the elephants’ faces (below), which allowed the Janjaweed to quickly obtain the elephants’ tusks. (Many elephant poachers now use chainsaws for this purpose.) The Janjaweed have been selling elephant tusks for decades now to fund their warfare activities in Sudan. Sadly, organized elephant killings conducted with military tactics and weaponry are becoming increasingly common in Africa. It is important to remember, however, that many elephants in Cameroon are not murdered by highly organized foreign militias, but instead by Cameroonian poachers. For example, in June 2012, three men from the Cameroonian military were caught poaching elephants inside Campo Ma’an National Park, located in the country’s South region.

For more information on the Bushmeat Crisis and Wildlife Crime, visit the Bushmeat Crisis Task Force at www.bushmeat.org and the Last Great Ape Organization at www.laga-enforecement.org. You are also welcome to email Sean Denny at sean.m.denny@gmail.com.

Below lists just some of the species that are protected by law in Cameroon. Unfortunately, despite the fact that these species are officially protected, some have already become extinct within Cameroon, such as the cheetah and black rhinoceros.

Mammals

-Lion

-Leopard

-Cheetah

-Caracal

-Zorilla (also known as the striped pole cat)

-African wild dog

-Gorilla

-Chimpanzee

-Drill

-Mandrill

-Guereza (also know as the Eastern black-and-white colobus)

-Preuss’s red colobus

-Preuss’s monkey

-De Brazza’s monkey

-L’Hoest’s monkey

-Agile Mangabey

-Angwantibo

-Bosman’s potto

-Cross River Allen’s galago

-Aardvark

-Giant ground pangolin

-African manatee

-Beecroft’s flying squirrel

-African savannah elephant

-African forest elephant

-Black rhinoceros

-Giraffe

-Red-fronted gazelle

-Yellow-backed duiker

-Mountain reedbuck

-Hippopotamus

-Topi

-Water chevrotain

-Eland

-Bongo

-Forest buffalo

-Roan antelope

-Hartebeest

-Sitatunga

-Bushbuck

-Defassa waterbuck

-Giant forest hog

-Bush pig

-Warthog

-African civet

-Genet (all species)

-Serval

-Chawless otter

-Bay duiker

-Peter’s and Harvey’s duiker

-Spotted hyena

-Striped hyena

-All other monkey species in Cameroon

Reptiles

-Long-snouted crocodile

-Nile crocodile

-African dwarf crocodile

-Green turtle

-Olive ridley turtle

-Leatherback turtle

-African spurred tortoise

-Eisentrau chameleon

-Pfeffer’s chameleon

-Four-horned chameleon

-Mount Lefo chameleon

-African rock python

-Royal python

-Muller’s sand boa

-Burrowing python

-Egyptian cobra

-Spitting cobra

-Black mamba

-Black cobra

-Green cobra

-Burrowing cobra

-Nile monitor lizard

-African savannah monitor lizard

-Bell’s hinged tortoise

-Common tortoise

-Elegant turtle

-Senegal turtle

-African turtle

Amphibians

-Goliath frog

Birds

-African gray parrot

-Ostrich

-Brown parrot

-Red-fronted parrot

-Senegal parrot

-Cameroon mountain pigeon

-Bannerman’s turaco

-Yellow-casqued wattled hornbill

-Grey-necked rock fowl

-Mount Kupe bush shrike

-Cameroon mountain francolin

-Lesser flamingo

-Greater flamingo

-Cameroon montane greenbul

-Dja river warbler

-Nubian bustard

-White stork

-Black stork

-Saddle-billed stork

-Crowned crane

-Secretary bird

-Green turaco

-Yellow-billed turaco

-Almost all birds of prey found in the northern half of the country. Eagles, hawks, falcons, and vultures are all birds of prey.

Monday, September 9, 2013

Then we flew to Barcelona

Spain is a place we’ve always sworn to visit “one day.” We love the wine, we love the food, we love the occasional Anthony Bourdain visits shown on television. We’ve always wanted to go, and figured we’d get there “eventually.” When our plans to leave Cameroon in June collapsed colossally and two of our dearest, most beloved friends invited us to join them on their way home via Barcelona, we took it for granted that this would be our silver lining. During the hardest days as our time in Cameroon came to a close, we would sing “Barcelona!” to the tune of the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah.

We landed at nearly midnight, found our tragically dirty luggage (giant camping backpack behind, standard sized backpack up front, and, oh, yeah, duffle bags, etc., over each shoulder), and hobbled to the taxi stand. After collapsing in bed in our little efficiency apartment, we woke to find ourselves in a land of sunshine and joy. Glorious, dignified old apartment buildings stretched upward on every street, offering comfortable shade, while balcony windows dripped with verdure. Occasionally a fine cooling mist would drift down on us as apartment dwellers nurtured their mini gardens above. We walked seven or eight miles every day, reveling in the freedom to do so, marveling when cars and busses and even the occasional motorcycle stopped at the edges of crosswalks and waited patiently for us to pass by. Barcelona is by far the most walking and biking friendly city we’ve been in. We ate asparagus and strawberries and cherries and bibb lettuce and all the things that were something other than the slightly over-ripe Roma tomatoes, onions, and garlic we’d had in everything for two years. We laughed, overcome by the absolute joy, and at the absurdity of being so overjoyed at the taste of a perfectly ripened strawberry, and tried not to drool over the delicious abundance and possibility down every aisle of the Mercat de La Boqueria.

We needed the time to reintroduce ourselves to Western culture. Daily the conversation would ensue:

Friend 1, ‘Do you think there’s a bathroom?”

Friend 2, doubtfully, ‘Mmm… probably…?”

Friend 3, ‘I’ll go check.’

Friend 3 absents and, after a brief interval, returns.

Friends 1, 2 and 4 look on expectantly.

Friend 3, ‘There was a bathroom!’

Friend 1, ‘How was it? Was it clean?’

Friend 2, ‘Was there toilet paper?’

Friend 4, ‘Was there water?’

Friend 3, “Yes, yes, and yes.’

All sit and grin like lunatics at the greatness of such an unexpected convenience.

We also needed to begin the readjustment process to shopping (as in, simply buying basic necessities). We needed new toothbrushes and walked into a supermarket. We made a beeline through rows upon rows of random things to the toiletries aisle. Apparently, one does not simply purchase a toothbrush. What kind of toothbrush did we want? What kind of toothbrush best represented each of us as a unique individual? There were toothbrushes of every color on the spectrum. There were flat headed ones, round headed ones, bristles that changed color, handle with or without grips, ridged ones, spiny ones, rubberized ones, vibrating ones, weird grippy things on the backs of the heads, inexplicable pointy things that flipped out from the handle. Are we still looking at toothbrushes?? After a moment of panic Kiyomi grabbed the two immediately in her direct field of vision and asked Jack, “Red or green?” Decision made. Crisis averted. All around reintegration success! We bought toothbrushes.

In Sagrada Familia we found a place that met, and perhaps even surpassed the majesty of Istandbul’s Blue Mosque. In simple human terms, the structure was first imagined by Gaudi in the 1880s, and is finally set for completion in 2026, following the design and instructions left behind in a feat that has transcended time, war, politics, religion, secularization, generations. When we first visited the basilica, we ran into a four hour line in the sun to purchase tickets, so we just walked around the outside. The Nativity façade at the back of the church (from the current tourist entry) shows the birth of Christ as the ultimate culmination of nature. Visions of the natural world – vines, animals, doves flying between abstractions of fruit and flowers, giant turtles or tortoises supporting the whole thing on their armored backs - climb the building, which stretches up, it seems, as far as the eye can see, culminating in a giant, richly green Tree of Life, reminiscent of an archetypal Christmas tree. In the midst of all the edenic (yeah, I made up a word) glory sits the artfully sculpted holy family in traditional stance. By contrast, the Passion façade is almost austere, with human figures rendered in spare abstraction meant to be reminiscent of skeletons (like the Deathly Hallows in Hermione’s telling of the story in the Harry Potter movie) gathered around a crucifixion. We, of course, bought tickets online to go inside the next day. Inside, it is as though Gaudi was the inspiration for every depiction of elfin architecture ever filmed. Stained glass colors the light green and red as you walk between support pillars designed to resemble massive tree trucks, drawing the eye up and up and up to a ceiling carved in leaf design and windows that let in a gentle, dappled sunlight. It makes you feel small and insignificant in the very best way; the way of spaces that are truly magical, that are holy, that are reverence itself. Each of us, with our varying degrees of traditional faith, varying degrees of question and doubt and trust and unknowing, found ourselves, in our own space, in our own time, pausing, deeply moved, feeling a sense of connection, of mystery, of some great unknown peacefulness.

Our week went too quickly, and, as at every stop on our way home, we found ourselves promising, “next time…” and “when we come back…”

Paris was waiting.

Monday, August 19, 2013

And we landed in Istanbul

Which is far too wonderful for how little we’ve been told about how it should be top ten on anyone’s bucket list of places to visit (are those still a thing?).

We got off the plane with a ten hour layover ahead of us and plans to take the Turkish Airlines-provided tour of the city and lunch. After quite a bit of wandering around (it seemed like every line would lead through a security check with no guarantee we were getting where we wanted to be, or that we could come back) and five very kind, very patient members of airport staff maintaining that, tour or no, if we wanted to enter into their country, we would, in fact, need a visa, we made it to the Starbucks (hey, we’re still Americans) on the other side of the immigration check (incidentally, thanks to our confusion, we were able to direct three other families to the lines they needed to be in). We got our bearings, only to learn we’d just missed the tour, but we met up with a few other returning volunteers and set out to explore on our own.

We took the tram to the Grand Bazaar. The city we saw fly by us was clean, warm, bright, an intriguing mix of pastel skyscrapers and the pregnant domes of neighborhood mosques. Nobody stared at us. No one seemed to find the group of us, obvious tourists, the least bit interesting – we reveled in our anonymity. The Grand Bazaar was both of those things, and it was easy to imagine the city centuries ago as a center of world trade, culture, education. We saw only a small bit of what was there, but we easily could have spent the entire day exploring if we weren’t all so hungry by that point. We came out of the Bazaar and crossed the street, considering the pictures of meals posted outside of various eateries, when an older man introduced himself in flawless English as the owner of the tea shop across the street. He placed our food orders for us in Turkish and then led us back to a little sun dappled avenue, shaded by grape vines, lined by low tables, peopled by old men engaged in an older dice game while sipping hot tea. We were sure we’d stumbled into some antechamber of paradise.

The proprietor brought us all hot tea in small curved glasses and moments later, our food was delivered from across the street. We could not have been more content than in those moments, but when the meal was done, we wanted to make sure we saw more of the city in our dwindling hours there.

And we were rewarded for our effort. We walked to the Sultanahmet (Blue) Mosque (which really is blue), and directly across a wide park, the Hagia Sophia. With its towering minarets and nine enormous domes, the mosque is an impressive building just to look at, more impressive when you consider it’s four hundred years old; but inside is where you really experience the majesty of it. We were asked to remove our shoes and checked to be sure we were appropriately dressed (no exposed legs or shoulders for women or men; but there are robes and wraps available so everyone can go in). Our voices dropped to whispers instinctively when we walked in. Our eyes were immediately drawn up by the at times ornate, and at times perfect simplicity of the dominantly blue tile work. The main dome swooping gracefully overhead felt protective. Blue, our impromptu guide told us, is the color of good fortune. This, we felt, standing there in socks and borrowed wraps, was reverent, was worshipful, and put one in mind of the majesty of the Divine. We couldn’t think of a church that could compare.

Due to time, we were unfortunately not able to go inside the Hagia Sophia, but we promised ourselves, “next time.” Yet, having always wanted to visit, and never (not really) expecting to get there, standing in front of the ancient basilica dedicated to the Holy Wisdom of God and modern day repository of culture and knowledge was a privilege.

From there, our clock was running out, but we and our fellow sojourners squeezed in a toast, after climbing up, and up, and up (and up again!) to the terrace at the top of a restaurant (the waiter smiling to himself the whole way… he knew what he was giving us), where we sat in a perfect, warm breeze and sipped some of the local brew, and took in a view of the Blue Mosque to our right and the Hagia Sophia to our left, and beyond that, the Sea of Marmara, and beyond that… oh, only Asia.

Tuesday, July 23, 2013

Heading for Re-Entry

After two long years we finally left Cameroon and are on our way home. The day was full of packing, repacking, throwing stuff in “up for grabs” for the volunteers we were leaving behind, cursing the accumulation of two years of stuff and using our mad Tetris skills to fit it all into two camping backpacks, two Camel-Baks, and one medium duffle bag. We had many final meals and final drinks and final hugs and tearful goodbyes and were drained by the time we stumbled into the airport – the taxi driver tried to change the price on us at the last minute and insist that it wasn’t normal practice to drive us up to the terminal building, just for good measure. After having our passports checked no fewer than five times, a couple meltdowns, and having a bottle of water purchased inside half of the “security checks” confiscated, we boarded the plane.

We flew for about forty five minutes and landed in Douala, where we waited for passengers to deplane, the plane to be cleaned around us, a crew change, and more passengers to board for an interminable hour. Fellow passengers treated the plane like any other mode of transport, leaning out of their seats to flag flight attendants like vendors who crowd every bus or bush taxi at every check point, village, or bend in the road, with commands of, “give me this,” or “bring me that.” The boy next to Kiyomi, though he was of narrow build, tried to take up not only his own, but also her seat, legs splayed wide under the arm rest and elbow and shoulder angled in above it. Finally sometime between three and four in the morning we left Cameroon air space and landed a few hours later in Istanbul.

A note on airplane food: it is amazing. The first bite of spinach nearly brought tears to our eyes.

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Home:Coming!

We are leaving Cameroon July 19th.

It was a rather long and arduous process to get that date settled over the late spring. Much more difficult than it should have been. And while it’s a few weeks later than what we would have preferred, we’ve made the best of it.

Our journey home will take us though a week in Spain with good friends we’ve made here, a few days in France visiting an old friend, and then for two weeks in Dublin with Kiyomi’s mom and her partner (plans made in April a year ago and looked forward to ever since!).

Finally, we’ll be back in the States on August 15th, and it’s about time! Two years without ever visiting home may not sound like such a long time, but two years of being foreign, alien, permanently outside and other, is at the very least exhausting. And while it’s been good and bad and hard and fun and worth it and so not worth it, we have the feeling it may take a little time to put better words to all of this.

Our last week in town will be a bit more busy than we expected. We’d been told to close our house and had made some plans to try to sell some of our larger furniture to other volunteers a month ago, when Peace Corps offered us a huge relief by deciding to keep our house. Then with less than two weeks left in town, and it being largely impossible to make arrangements to sell anything at this point, Peace Corps told us last week that they’d changed their minds again and won’t be keeping our house. But they are keeping another house and will take our furnishings for that one, though we suspect Peace Corps moving our house will really involve a lot of us hauling furniture and boxes (thanks to the packages we’ve received over the years, we have boxes to pack things up in! And our Air Force upbringing makes us old pros at moving house). It wouldn’t be quite so bad if we weren’t also trying to do all the other things involved with leaving a place – saying goodbye to friends, visiting favorite places a last time, last minute souvenir shopping, writing our final Volunteer Reports and Descriptions of Service, making purchases for our travel, closing our bank accounts, getting signatures to say everything is properly in order, rechecking and editing our resumes, putting out feelers for new jobs, an apartment, and on.

But, as this is written on July 5th, in 9 days and counting, come what may this will all be done, and we’ll be going through our final medical evaluations in Yaounde to leave here at the end of that week.

Friday, March 22, 2013

…it’s a street in a strange world…

We haven’t made a secret of the fact that our Peace Corps service has not been what we anticipated; we prepared, unintentionally and unwittingly, for one experience and have had quite a different one. Still, we would join Peace Corps again. We would even come to Cameroon again.

If you’re considering it, don’t join Peace Corps for the work. It can be useful if you don’t have a lot of work experience, and (we’ve read) employers do recognize that they’re getting certain benefits, like the willingness to take risks, tackle challenges, and make due with limited/no resources or budget, when they hire RPCVs. But don’t come only, or even primarily for “the hardest job you’ll ever love” – because if you’ve had a few years in the work force doing something you find at all rewarding or engaging, this won’t be it. Working in Cameroon is hard, disheartening, discouraging, sometimes utterly defeating when you’re doing it right, and you have to be willing (able?) to squeeze every ounce of satisfaction out of the tiniest victories (Started only an hour late! Half the people expected showed up! Counterpart did what they said they would do!), or the very basic knowledge that at least you did everything you could when nothing works out. The benefits are much more of the Goals 2 and 3 variety. We have long been proponents of study abroad and international travel as an essential piece of any education. We are in a global world now, and it just keeps getting smaller – resources we take for granted are not going to last forever, and the habitable landscape is dwindling – that means we have to figure out how to tolerate each other on just a basic level, let alone the enormous benefits of increased innovation, new perspectives, appreciation of beauty and depth of understanding to be gained by even a small experience of another culture. If you missed out on study abroad in college, Peace Corps is much harder, dirtier and longer, but definitely a good path to pursuing your global education.

Our time in Cameroon has taught us a lot. Both anthropology majors in school, we’d been warned against ethnocentrism and cultural relativism for years, but it’s been an education of a different sort to try to understand a fundamentally and completely different mindset. Things we’ve taken for granted, like, “everyone wants their children to be better off than they were,” or “le’s all pitch in and work hard for a common goal,” just don’t at all translate. But we’ve learned to just say, “okay” to both the mind-boggling and the merely confusing. Sometimes understanding isn’t enough, and sometimes it isn’t possible, and things are still going to be exactly as they’re going to be in that moment. And that’s…okay. We’ve mentioned before the gained understanding of just how complex issues in the developing world (at least this corner of it) really are – it’s actually not a simple issue of lack of ideas, passionate individuals, cultural sensitivity, or resources. It’s a million and one little things, alongside enormous social and political challenges that are not going to be solved in two years, or twenty, or maybe more. And as we’ve said before, these things aren’t going to be answered from the outside in – the best and most sustainable answers, we believe, are going to come from the Cameroonian people when and how they are ready to do it.

On a personal level, we feel that we’ve grown, maybe matured a bit, certainly mellowed. Once you can accept, “okay,” and stop fighting what doesn’t make sense, not much is really going to ruffle you very easily. Cell phone companies, watch out! Because forty-five minutes on hold has got nothing on anything in Peace Corps. Beyond that, it’s been an incredible time to reflect on what matters, to gain some distance and perspective on issues from our “past lives,” and focus in on what we want in our future. Running water is a must; hot, if possible; electricity we could mostly do without as long as we can charge stuff now and again. Plus, we’ve made some amazing friends who will be part of our lives forever.

If you’re thinking about coming, think in terms of personal growth and international perspective, not work opportunities. Be prepared for periods of symptoms strongly resembling clinical depressing for at least a few months out of the twenty-seven – no, there’s nothing wrong with your thyroid, you’re just sleeping for eleven hours because your brain needs a break. (Seriously, though, if you think you may be sick or really do struggle to get through the day, call the medical office.) We think Cameroon is better suited as a post for people who are very extroverted and enjoy small talk over drinks with strangers. Comfort with heavy alcohol consumption around you is a must, and “taking” beers is pretty important to socializing in this culture. If you’re female, you will be sexually harassed, and it can get pretty intense pretty fast – fair warning. You might get more out of the work here if you haven’t had a lot of work experience yet and are looking to build your resume – otherwise, be very comfortable setting boundaries around not being “whiteman window dressing.” In fact, being very comfortable setting boundaries is important – here and in life. Pick that skill up. It’ll be easier here if you have a flexible definition of personal space (the music you play on your iPod… that’s all you get), possibly grew up on a farm/can tolerate roosters, and really can just go with the flow – by which we mean, you’re not someone who cares about having a plan, how long meetings run, waiting for vehicles to be pushed out of four feet of mud every five hundred yards, being asked for everything you own, or nobody calling you by your name after two years. If you don’t think that’s you, consider saying no to a posting in Cameroon. Chances are good your placement officer will be calling you again in a few weeks with another post to consider.

And that’s all for now! Next up, find out when we’re coming home!

Saturday, March 9, 2013

Hello World! It’s been a while

We are in our last few months in Cameroon now, and it’s strange. We’re trying to make notes of “The Last Time That…” For example, the last time we’ll eat fufu and njama njama is yet to come, but sure to be nostalgic – or will we even realize that it is the last time? (Not to worry, we have ideas for how to make it with an American twist when we get home, and we’ll post recipes once they’ve been suitable tested on our family.) Our last visit to Azam Hotel for pizza has probably already happened. The last time we traveled to Limbe has already come and gone, and this week we made reservations for our last trip to Kribi.

Everywhere we went on our Great Gaines and Losses Farewell Tour that launched this blog and our Peace Corps adventure, we were able to talk about, “when we get back.” Even in our other travels to the Caribbean and Central American and even Europe, we’ve always thought in terms of “one day we’ll be back,” there’s always another visit on the horizon in our minds, another chance to experience our favorite things or get in those experiences we missed the first time through. Yet somehow, coming to Africa it seems is psychologically a further trip to make, a greater distance that leads us to suspect, while we fully intend to see other parts of this great continent, we won’t be coming back to Cameroon. So we’re trying to soak up every favorite part of this experience that we can, to make sure we visit our favorite chop houses and views and places “one last time,” and to make sure that there isn’t anything we’ll regret “if only we’d made time for…” Our “six-ish more months” has now dwindled by half, so we’re doing our best with figuring out how to say goodbye to the place that’s been our home for two years.